Changing Higher Education Financing: Small Changes for Big Wins

Jonathan McCain

Abstract

In 2019, the federal government issued $76 billion in new loans to 7.6 million students. It is estimated that the amount of student loans totalled $1.4 trillion in 2019 (CBO, 2020). This figure represents a financial burden for millions of American households, while also indicating the presence of missed economic opportunities. Due to the current gridlock in Congress, it is difficult to make the major moves necessary to address this looming economic giant. This paper will suggest small changes that can be made in the federal education loan system to bring big wins to American families.

Introduction

Higher education and education beyond grade 12 in the American system are linked to a higher quality of life for the citizenry. Higher education is linked to strong economic growth and thriving communities (Jackson, 2020). Public colleges and universities are responsible for educating our teachers, nurses, and social workers, individuals who contribute to a better society (Jackson, 2020). Current research suggests that individuals who complete their bachelor’s degree contribute to lower levels of unemployment, lower levels of incarceration, and higher levels of civic participation (Jackson, 2020). Funding education is vital to a strong functioning society. This policy memo will consider government actions that will increase access to higher education for all citizens. At the same time, this policy memo will address potential changes that could be made to the current system that decrease inefficiencies and increase the social benefits of funding higher education.

The Problems of Funding Higher Education

Policy Problem 1: Higher Education Funding Cuts Coupled with Increased Costs

The economic conditions for funding higher education in the United States can appear contradictory. Previous policy research has indicated that the Great Recession of 2008 contributed to nationwide budget cuts to education (Jackson, 2020). Between 2008 and 2019, funding for education fell by $3.4 billion with thirty-seven states cutting education funding from their budgets (Jackson, 2020). At the same time, the cost of public tuition rose at a rate of $2,576. In some states, the increase was indicated to be at a rate of 50% (Jackson, 2020). Even the costs of community colleges were found to have increased by $1,096. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, states have moved towards continuing the trend of cutting education funding. Data suggests that the cost of higher education will continue to increase. In 2019, the federal government issued $76 billion in new loans to 7.6 million students. It is estimated that the amount of student loans totalled $1.4 trillion in 2019 (CBO, 2020).

There is no debate that we as a society want to increase access to higher education for all citizens. However, the increasing costs of higher education represents a barrier to low-income, and even middle-class, individuals. If access to higher education is restricted, then society is less likely to reap the benefits associated with higher education. As governments continue to decrease their educational funding, the burden of the cost of higher education will continue to be pushed onto the individual.

Policy Problem 2: The Opportunity Costs of Student Debt

While research suggests that state governments are cutting education funding, The United States of America’s federal government has utilized grants and loans to fund the higher educational pursuits of the citizenry. Grant money does not have to be paid back and can be distributed based on economic status, merit, and other factors. Loans, on the other hand, have to be repaid by the recipient. Currently, the United States has an outstanding loan balance of $1.5 trillion (Office of Federal Student Aid, 2018). This figure indicates that the presence of student loan debt is generating a drain on economic activity. In other words, money that is being used to pay off student loan debt could be utilized for other economic purposes, creating a huge opportunity cost.

The Federal Office of Student Aid (FSA) housed in the U.S Department of Education is responsible for administering the student loan program, which currently has $1.1 billion in outstanding loans affecting 34 million borrowers (Campbell, 2019). Student loans are currently administered by having private contractors “service”, or manage student accounts (Campbell, 2019). This current system of administration costs the United States $2 billion annually (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). The FSA utilizes private collection agencies (PCAs) to obtain repayment, costing $1 billion annually (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2019). While the cost of $2 billion is going towards education, which research has shown has a plethora of positive social benefits, there are still inefficiencies present in the current system, generating opportunity costs for federal and state governments and negatively impacting individuals.

The U.S. federal government is required to spend $1 billion annually collecting repayment for student loans (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). The opportunity costs associated with this $1 billion cannot be ignored. Alternate employment of these funds could be for social programs and investment instead of repayment collection by the government. Some may argue that this is a necessary outcome; however, while student loans increase access to higher education for low to middle-income families, some students can find themselves unable to pay back the loan or default ( Campbell, 2019). Currently, 7 million accounts are in default status (Campbell, 2018). These statistics represent a drain on economic activity within the United States, in addition to money the federal government does not recover.

Policy Problem Summary

It is necessary to fund education. If this necessity was not clear, the funding of K-12 education would not be as politically palatable as it is. However, current economic conditions have generated a need to go beyond the K-12 level. Modern employment opportunities are linked to the obtaining of a bachelor’s degree or higher. However, governments have continued to make cuts to fund higher education contributing to increased higher education costs, in addition to other factors that have contributed to higher education costs. While the current policy for this problem is to provide individuals with grants and loan assistance in covering these costs, this policy action has outcomes that are contributing to opportunity costs to the individual, the federal government, and state governments.

Policy Goals

This policy memo will research policy actions that accomplish the following:

Increase access to higher education for the American citizenry

Decrease opportunity costs associated with student loan debt (see Policy Problem 2: The Opportunity Costs of Student Debt)

Decrease the number of student loan debt accounts that are in default

Lower costs to federal and other governmental entities

Policies that are effective at achieving these goals will generate the positive externalities generated by higher education, while also decreasing the economic suppression created by the opportunity costs of student loan debt and associated negative externalities.

Policy Criteria

With the goals mentioned above in mind (see Policy Goals), the following policy options will be evaluated from the following criteria:

Increases enrollment of students in higher education

Decrease costs to the federal government

Politically viable for Implementation

Increased enrollment of students in higher education ( universities, community colleges, trade education, etc.) is directly linked to increased access. If there is more access to higher education, then the positive externalities of higher education are more likely to be achieved. For simplicity of analysis, this memo will not address graduation or retention rates in evaluating policy. However, it will be assumed that there are accountability mechanisms in place to ensure degree attainment and certification are occurring (Wellman, 2016).

Decreased costs to the government seem not to need lengthy justification. Policy options should decrease the costs associated with the federal government, as these economic costs are generating the opportunity costs in the first place.

Political viability must be considered. If the change cannot be made in the first place, then the proposed increase in benefits and decrease in costs cannot be achieved. In addition, if the proposed changes are dependent on which political party is in power, the funding landscape of higher education could be destabilized, generating more problems for the federal government, state governments, and American citizens.

Policy Option 1: Maintain the Status Quo

The federal government and state governments have the option not to make any changes to the current system. The federal government has increased funding the institutions of higher education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the current system has increased access to higher education for millions of citizens (Jackson, 2o2o). For example, people of colour (African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, etc.) now make up 40% of the student population at public universities (Jackson, 2020). There is no denying that the explosion of student debt in the United States is linked to more citizens attending higher education institutions.

The option of maintaining the status quo will not address the inefficiencies in the current system for funding higher education. Studies suggest that tuition costs will continue to rise, leading to the need for more student lending (Jackson, 2020); this statistic suggests that at some point, the U.S. federal government will be spending more than the $2 billion annually that is loaned to student borrowers. In addition, the policy option of maintaining the status quo will likely lead to the need to increase the amount of money contracted to private collection agencies, especially as the number of student borrowers increases. All in all, allowing the current policies to run their course will not address the opportunity costs present and are susceptible to increasing costs in the future.

Maintaining the status quo is not politically viable. Progressives are concerned with opportunity and access, especially for minority students and students from low-income families. They favor policies that reduce or eliminate the financial burden associated with attending college for these groups (Huelsman, 2019). On the other hand, Conservatives are concerned with the rising student loan debt and the potential liability this represents to taxpayers (Amslem, 2019). The current system, which generates large amounts of debt for low-income and middle-class families, is not popular with those who identify as progressive. Furthermore, conservatives are wary of the current system as costs are increasing not only to government institutions but also to the individual taxpayer. The policy option of maintaining the status quo or doing nothing is not effective in decreasing the opportunity costs associated with higher education financing, nor does it address political wants.

Policy Option 2: Eliminate the Use of Private Collection Agencies

Seven million student loan accounts are in default, meaning the federal government is not recovering the money it has loaned out. The United States government spends $1 billion annually for contractors to obtain these payments (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). The policy option of eliminating the use of private collection agencies could address the opportunity cost of $1 billion that is occurring within the current system.

The current costs of using private collection agencies (PCAs) for the seven million accounts in default is equivalent to the amount of money spent on the thirty-three million accounts in good standing with loan servicers (Campbell, 2019). PCAs differ from federal loan servicers in that they can utilise more aggressive means to obtain repayment, such as withholding tax refunds, wage garnishment, etc. ( Campbell, 2019). This action stifles individual economic activity as the individual has less money to spend. There is research that suggests that low-income individuals and people of colour are more likely to experience default on their loans (Campbell, 2019). If higher education funding was meant to increase access for this group of individuals, why utilize a system that is creating more problems on the backend?

Policy research also indicates that the cost of using PCAs is not beneficial to the federal government. Only 4% of student loan repayment, or $354 million, was made through these institutions (Campbell, 2019). According to an analysis by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the federal government is paying $40 for every $1 of student loan debt obtained, representing a bad return on investment for the taxpayer (Campbell, 2019). On top of this bad return on investment, PCAs do not set up student loan borrowers for success in the long term. The CFPB found in 2017, that at least 40% of rehabilitated borrowers were at risk of default within three years ( Campbell, 2019). The cost of PCAs also burdens the individual in default. Federal law requires that individuals pay collection costs (Campbell, 2019). Due to the nature of these collection costs, 20% of an individual’s money for repayment is applied to these fees instead of the defaulted amount (Campbell, 2o19).

Due to the inefficiencies and the costs associated with PCAs, it would be reasonable to eliminate them from use, freeing up millions of dollars for other uses. Federal loan servicers could provide the same services as PCAs (Campbell, 2019). These services include contacting delinquent borrowers, loan counselling, and reporting accounts to the federal government (which could allow for wage garnishment) (Campbell, 2019). In other words, the federal government is wasting hundreds of millions of dollars paying outside agencies to do what federal loan servicers could do in the first place. Students in default would not get off without consequences. However, the use of loan servicers instead of PCAs would drastically reduce, if not eliminate, the collection fee costs (Campbell, 2019).

While the policy option of eliminating PCAs does not restructure the current financing system on the front end, this action could save the federal government up to $1 billion annually. This money could be reinvested into federal loan servicers to provide better service to student borrowers ( Campbell, 2019). However, this reinvestment is not required. The $1 billion saved by this policy option could be reinvested in other programs shown to be beneficial.

The political viability of this policy option is high. Since the program represents savings for the federal government, if not a reduction in the alleged size of government, this policy option should appeal to conservatives. On the other hand, progressives will notice that this policy action is beneficial to low-income and minority groups, which appeals to their political sensibilities. However, due to the low visibility of PCAs, industry lobbying can affect what actions are taken. Previous Education Secretary Devos favoured policies that profited PCAs (Campbell, 2o19). To combat industry influence, the visibility of this issue will have to increase among the public.

Policy Option 3: Change Repayment Plan Default to Income-Driven

The status quo of higher education financing involves accessing, obtaining, and repaying funds. Assuming the complete systemic overhaul is unlikely, if not impossible, only small policy actions are likely to be implemented to allow for change.

To decrease the opportunity costs of student loans, policy focus can be shifted to the individual. One such policy that could decrease opportunity costs for the individual is to change the default repayment plan to income-driven repayment.

Income-driven repayment plans reduce required monthly payments for borrowers who may have either low income or a large balance ( CBO, 2020). Income-driven repayment plans require 10 to 15 percent of a student’s discretionary income, typically under a ten-year fixed plan. In addition, borrowers who fail to repay their loans within a twenty to twenty-five-year period may have the outstanding balance forgiven ( CBO, 2020). It is estimated that $490.4 billion in loans will be repaid utilizing income-driven repayment plans ( CBO, 2020). From 2020-2029, loans repaid through income-driven plans would generate a $211.5 billion cost to the federal government. In contrast, maintaining the default fixed payment system would only generate a $51.4 billion cost (CBO, 2020).

Rejecting changing the default payment to income-driven appears to be predicated upon it generating higher costs for governmental institutions, which is the opposite of established policy goals and criteria ( see Policy Goals, Policy Criteria). It has already been firmly established that higher education generates a myriad of positive externalities to benefit American society ( see Introduction). If individuals view taking on student loan debt as manageable in the future, then it is reasonable to assume that they are more likely to engage in the higher education system. However, more research would be needed to determine if the increase in enrollment in higher education justifies the cost.

Switching to income-driven repayment plans does meet the policy goal of decreasing student loan accounts in default ( see Policy Goals ). Income-driven plans cost the borrowers less than the default payment plan ( CBO, 2020). Individuals with income-driven plans can handle the decreased amount in monthly payments.

While costs for the federal government increase, the cost to the individual decreases. The shift to income-driven repayment plans as the default minimizes cost to the borrower. More research is needed to determine if this decrease in cost to borrowers is enough to justify increasing the cost to the federal government. In other words, the project benefits to (presumably) economic activity must be more than $211.5 billion (over ten years).

The political viability of making this shift to income-driven repayment plans varies. The use of income-driven repayment plans has nonpartisan support, even within the status quo ( CBO, 2020). However, the increased costs to the federal government could ward off needed conservative support to make this transition. In contrast, progressive attitudes may align with this policy as low-income and minority groups are likely to benefit from this shift ( CBO, 2020; Campbell, 2019). Since federal loans are 100% directly funded by the federal government, private institutions are unlikely to lobby against changes in repayment policy (CBO, 2020; Campbell, 2019).

Policy Options Chart #1: Evaluation based on Criteria

Recommendation ( Policy Option #4): Elimination of PCAs Combined with Income-Driven Repayment Plans as the Default

Education is beneficial for American society. The need for education beyond K-12 is clear ( see Policy Problem Summary). The costs associated with higher education are increasing. The current system, while generating some success, has inefficiencies that can be addressed ( see Maintain the Status Quo). However, these inefficiencies, or opportunity costs, can be addressed. Operating under the assumption that total systemic change is unlikely due to polarization, small changes to the current system can be made to generate big changes.

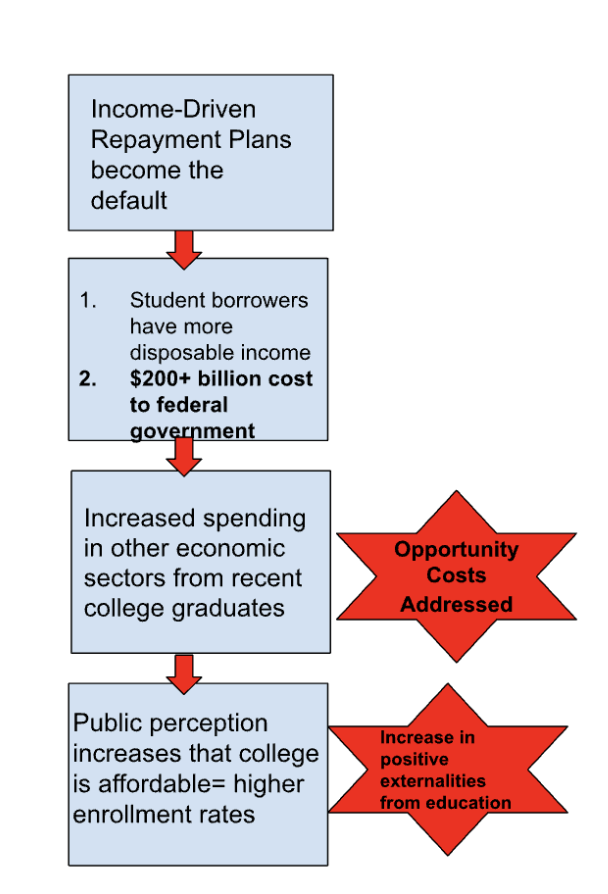

Private collection agencies should be eliminated. Private collection businesses utilize federal tax money for an activity that is not beneficial in the long run ( see Eliminate the Use of Private Collection Agencies). Federal loan servicers could perform the same activity utilizing the same funds more efficiently or maybe even at a lower cost to the American taxpayer. In addition, loan repayment should be defaulted to income-driven plans. There is no loss to the private sector since loans are 100% backed by the federal government. The cost to the federal government is $211.5 billion (over ten years). However, there is a possibility that the new economic activity of borrowers, generated by lower loan payments, could generate benefits that justify this cost. More research is needed. In addition, the perceived decrease in risk, again due to lower loan payments, could encourage more individuals to enter into higher education. Higher education is associated with a myriad of positive externalities ( Jackson, 2020). More research is needed to determine if the increase in higher education enrollment can justify these increased costs to the federal government. Figure I demonstrates how this policy action could contribute to both societal and individual benefits. Since the current status quo is set by the U.S. Department of Education and federal loan servicers, making income-driven plans the default does not represent an administrative hurdle. Since this policy action has bipartisan support, no political hurdles will be addressed.

Figure 1: Logic Flowchart of Changing Default Loan Repayment Methods

Private collection agencies should be eliminated. This policy action is more complex politically, administratively, and economically. Figure 2 captures the risks of this policy action and potential mitigation measures. Regardless, private collection businesses utilize federal tax money on an activity that is not beneficial in the long run ( see Eliminate the Use of Private Collection Agencies). Federal loan servicers could perform the same activity utilizing the same funds more efficiently, or maybe even at a lower cost to the American taxpayer. While $ 1 billion will no longer be going towards private entities, investment is needed into federal loan servicers since these institutions will be providing a new service, collecting debt. Research is needed to determine how much federal loan servicers will need to provide this service. While more research is needed into the total elimination of PCAs, current policy research indicates that federal loan servicers can handle debt repayment more efficiently, saving the government money in the long run. Figure 3 captures the logic behind the elimination of PCAs.

Figure 2: Risk Mitigation of Eliminating Private Collection Agencies

Figure 3: Logic flowchart of Eliminating PCAs

References

Amselem, M.C. (2019, June 20). Americans Deserve Bold Policy Reforms in the Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. Backgrounder, 3417. Retrieved May 22, 2021 from http://report.heritage.org/bg3417

Campbell, Colleen. (2019) “How Congress Can Fix Student Loan Repayment” May17th at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2019/03/07/467005/congress-can-fix-student-loan-repayment/

Congressional Budget Office (2020). Income-Driven Repayment Plans for Student Loans: Budgetary Costs and Policy Options Retrieved May 31st, 2021 from https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55968

Huelsman, M. (2019, June 6). Debt to Society: The Case for Bold, Equitable Student Loan Cancellation and Reform. Demos. Retrieved May 22, 2021 from https://www.demos.org/research/debt-to-society ‘

Jackson, Victoria (2021) “States Can Choose Better Path for Higher Education Funding in COVID-19 Recession” May 17th, 2021 at https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-can-choose-better-path-for-higher-education-funding-in-covid

Office of Federal Student Aid, “Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report” ( U.S. Department of Education, 2018), available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/2018report/fsa-report.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education, “Student Loans Overview, Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Proposal” (2019), available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget19/justifications/q-sloverview.pdf.

Wellman, Jane (2016) “Statewide Reforms in Higher Education Financing and Accountability: Emerging Lessons from the States” May 19th at https://collegefutures.org/publication/recent-statewide-reforms-in-higher-education-financing-and-accountability-emerging-lessons-from-the-states/