Ethiopia and Egypt: constructing an ‘enemy’ or eternal geopolitical contradictions? On interstate conflict without common borders.

Sergei Chernov

ጽድቅና ኵነኔ ቢኖርም ባይኖርም ከክፋት ደግነት ሳይሻል አይቀርም

(Ethiopian proverb: “Whether righteousness and torment do exist or not, generosity is better than iniquity”) (Ermias, 2020)

Abstract

For several reasons, 2024 saw an escalation in relations between Egypt and Ethiopia. The first is the issue of using Ethiopia’s Hidāsē dam. The second is Ethiopia's recognition of Somaliland to gain sea access. The disagreement between the two regional leaders appears to be temporary and situational, the reasons for the confrontation between these states go back a long way. The goal of this study is to identify the key factors influencing the Ethiopian-Egyptian conflict. The author concludes that Egypt and Ethiopia are facing each other as geopolitical adversaries but stand with their backs to each other as economic partners.

1. Historical context

Since antiquity, the valley of the great African river Nile has been not only the scene of fierce geopolitical rivalry between the Egyptians and the ‘Ethiopians’ (from the Greek Αἰθίοψ, ‘tanned, burnt face’) but also a place of active inter-civilisational interaction. The Egyptians moved steadily up the Nile through the rapids to expand their state’s borders and try to control the trade route from the Horn of Africa, which carried the flow of goods from Arabia and sub-Saharan Africa. Dynasties and millennia changed, but the geopolitical struggle for the Nile between the ‘mouth’ (North) and the ‘source’ (South) did not stop. Egypt often won, but sometimes, taking advantage of the weakening of a formidable rival, the South took revenge and even imposed its ‘Ethiopian’ dynasty on Egypt. However, it should be borne in mind that Ethiopia (aka ‘the kingdom of Kush’) in those times primarily understood the territory of modern Sudan. Ethiopia proper (Damaat, created by aliens from the Arabian Peninsula, then the kingdom of Axum as its successor) became one of the main geopolitical opponents of Egypt only at the turn of the millennium. The Roman Empire (and later Byzantium), having made Egypt its province, regarded Axum as the most important geopolitical actor in the region and had to reckon with its interests.

At the same time, the civilisational and cultural interaction between the North and South of the Nile Valley was mutually beneficial for a long period. For example, around 330 A.D., Axum became the third Christianised state in the world (after Armenia and the Roman Empire). Christianity and the Greek language came to Axum through Egypt. However, this fact became a factor in the serious civilisational situation after the conquest of Egypt by Muslim Arabs in the 7th century A.D. (Ethiopia remained independent and Christian). Speaking of the religious factor in Ethiopian–Egyptian relations, one cannot fail to mention that today, about 35 million Muslims live in Ethiopia, or about 31 percent of the country’s total population (World Population Review, 2024a). Conversely, Egypt is home to about 10 percent of the Christian population (World Population Review, 2024b). Such statistics result from cultural exchange and interaction over the course of historical development, but some researchers look at religious differences from another angle. For example, S. Huntington, in his famous work ‘The Clash of Civilisations,’ argues as follows: “Some Westerners, including President Bill Clinton, have argued that the West does not have problems with Islam but only with violent Islamist extremists. Fourteen hundred years of history demonstrate otherwise. The relations between Islam and Christianity, both Orthodox and Western, have often been stormy” (Huntington, 1996). From his point of view, Ethiopian-Egyptian contradictions can be explained by civilisational differences. On the other hand, it would be naive to assume that all the contradictions between the countries are merely cultural. One of the episodes of this rift was the Egyptian–Ethiopian war of the nineteenth century.

In the early 1870s, Egypt wanted to expand its territories in East Africa. At that time, Egypt was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. In the 1860s, Egypt received some Ottoman territories that became legally assigned to it. “In 1868 Turkey gave him the port of Massawa, and in the early 70's under Egyptian control was already the entire coast from Zeila to Guardafui. The plans of the khedive also included the expansion of Egyptian possessions at the expense of the north-eastern regions of Ethiopia” (Tsypkin & Yagua, 1989). In Ethiopia during that period, there was feudal fragmentation, as local rulers had more regional power than the emperor. The Egyptians saw this as an opportunity to seize new territories and expand their zone of influence.

The military campaign was unsuccessful for the Egyptian army, primarily because of the enemy’s numerical superiority. It is worth noting that the Ethiopian emperor tried to mobilise the population using religious factors. It is well known that Egypt is a Muslim country, and the majority of the Ethiopian population are Christians. That is why Emperor Yohannis spoke about the ‘expulsion of Muslims’ from the ancestral territory of the state. As a result, the war ended with the complete defeat of Egypt and the strengthening of the central power in Ethiopia. However, the peace treaty itself, mediated by the British Empire, was signed in 1884, giving great preference to Ethiopia (Ram, 2009).

Thus, although the disagreement between the two contemporary regional leaders, Egypt and Ethiopia, appears at first glance to be temporary and situational, the author suggests that, in reality, the reasons for the confrontation between these states go back a long way. In this struggle for influence, the author examines various aspects, such as economic, geopolitical, and military. The goal of this study is to identify the key factors influencing the contemporary Ethiopian–Egyptian conflict.

The methodology of this study relies primarily on the historical method (which examines any phenomenon and fact in its historical development) and comparative analysis.

The literature devoted to this topic includes a large number of scientific books and articles. Among them is the research of Erlich and Haggai ("Haile Sellassie and the Arabs, 1935-1936". 1994. Northeast African Studies, 1(1), 47–61; "Identity and Church: Ethiopian—Egyptian Dialogue, 1924-59". 2000. International Journal of Middle East Studies. 32(1): 23–46), Yihun, Belete Belachew ("Battle over the Nile: The Diplomatic Engagement between Ethiopia and Egypt, 1956-1991". 2024. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 8(1 & 2): 73–100), Ali, Faisal (Egypt backs Somalia in dispute over Ethiopia-Somaliland deal". 2024), and G. Markus, Harold (2002). A History of Ethiopia. Berkeley, California: University of California, etc.

Official sources also were used (for instance, (1) Brief History of Egyptian-Ethiopian relations - Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Egypt), (2) "Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan Should Negotiate Mutually Beneficial Agreement over Management of Nile Waters, Top Official Tells Security Council//UN Press," and (3) "Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Agreement within Reach, Under-Secretary-General Tells Security Council, as Trilateral Talks Proceed to Settle Remaining Differences//UN Press"), with additions of mass media articles (for instance, (1) Egypt and Ethiopia vow to defuse Blue Nile dam row. BBC News; (2) Nile Basin countries experts negotiation in Khartoum marked with disputes//Egypt Independent; (3) Ethiopia determined to construct Renaissance Dam: ambassador//Egypt Independent; (4) Ethiopian dam project to include Egypt and Sudan//Egypt Independent; and (5) Minister: Diversion of Blue Nile no indication that Egypt approves of dam//Egypt Independent etc.).

2. Current geopolitical context and the strengths of the parties

Egypt and Ethiopia are now contenders for the role of regional leadership in North East Africa. From the perspective of political realist theory, large states, in pursuit of their national interests and using instruments of force, inevitably seek to expand their dominance at the expense of their neighbours. The next section examines what are the forces of the parties.

2.1 The forces of the parties

Modern Egypt and Ethiopia are the strongest actors in the North-East Africa region. Ethiopia's population (about 120 million) is the largest in Africa (after Nigeria). Egypt's population is slightly smaller than Ethiopia's (about 110 million). However, Egypt’s GDP is significantly larger than Ethiopia’s. Ethiopia is also far behind Egypt on the Human Development Index (ranked 173rd versus Egypt's 116th). In addition, Ethiopia has much greater ethnic, linguistic (over 100 languages), and religious diversity (fraught with internal conflict) than Egypt. Arabs (Arabised Egyptians) comprise about 85% of Egypt's population (Coptic Christians 10–15%). In comparison, in Ethiopia, the largest peoples are Oromo (35% of the total population) and Amhara (25%), and Christians of all denominations make up only about 60% of the faithful. It is no coincidence that Ethiopia has been the scene of fierce inter-ethnic warfare for many years. However, Ethiopia's greatest geopolitical vulnerability is its lack of access to the sea, which was lost in 1993 after the Ethiopian province of Eritrea seceded following its bitter, long-running war of independence. A problem for Egypt is Islamic radicals actively fighting the country's government (especially in the Sinai Peninsula). So, it is not surprising that both Ethiopia and Egypt spend quite a lot of money on their armed forces.

Many rankings in the world compare the armed forces of different countries. The Army Strength Index takes into account more than 50 criteria, so it can be taken as one of the most detailed ones. According to the latest Army Strength Index, Egypt is ranked 15th with a score of 0.2283, while Ethiopia is ranked 49th at 0.7938 (Global Firepower, 2024). Of course, it can be noted that this index is not the only or completely objective index. However, it can help us analyse and compare the forces in the region.

Comparing the capabilities of Ethiopia and Egypt is necessary for several reasons. First, it assesses the prospect of open confrontation in the future. Second, it enables us to understand which side can use economic and military superiority as an instrument of political pressure.

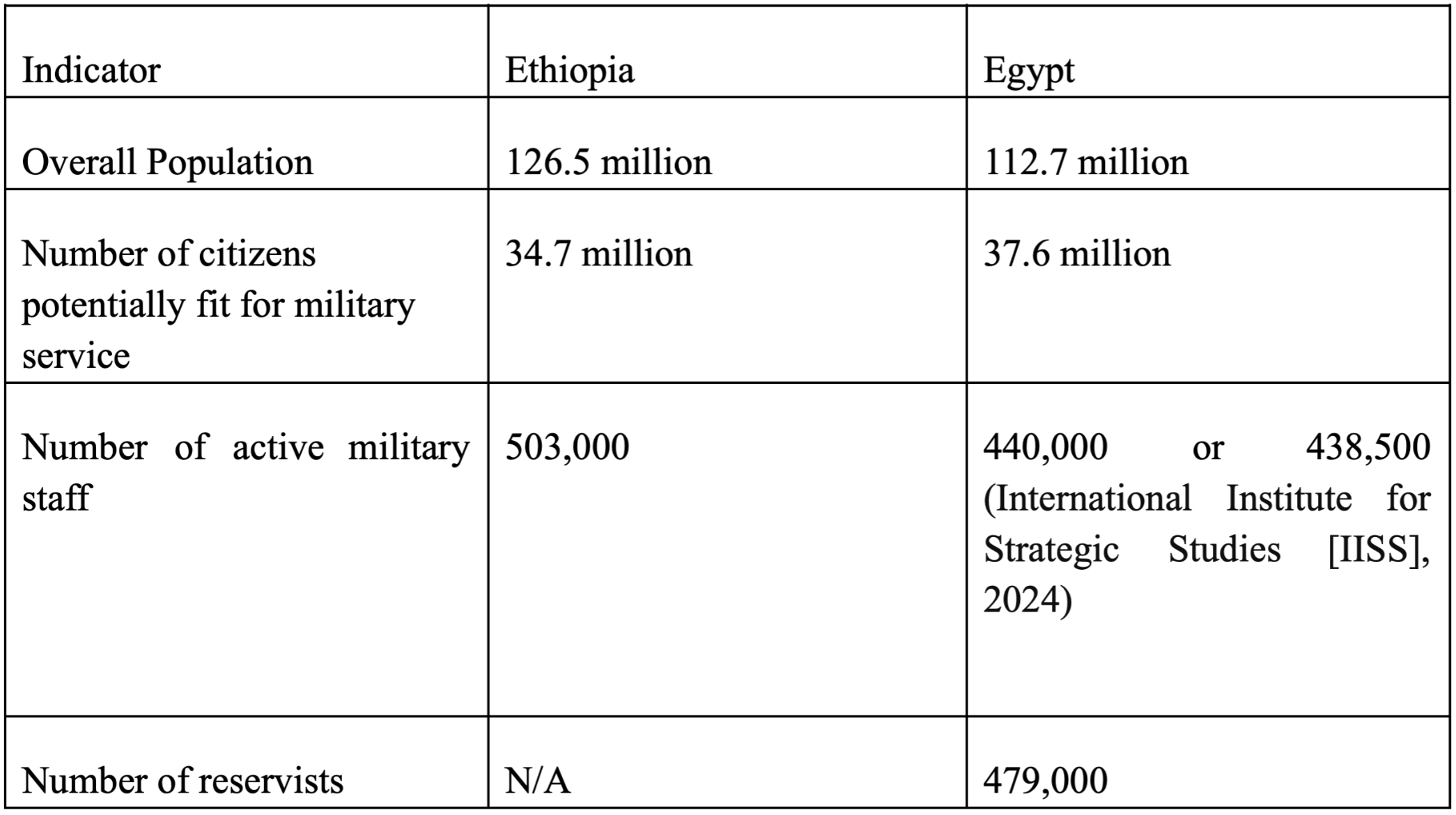

Table 1. Comparison between Ethiopia and Egypt in 2023.

Table compiled by the author based on the Encyclopedia of Countries and Cities (2024a).

Both countries have comparable populations, and in the case of general mobilisation we can call the conditions equal. The number of professional military personnel also does not differ enough to speak of any significant superiority. In Egypt, military service is compulsory for 18 to 36 months for men between the ages of 18 and 30, who then become reserves for 9 years (World Population Review, 2024c). Ethiopia has no compulsory military service. Thus, Egypt has some advantages in this aspect.

Table 2. Quantity of types of weapons.

Table compiled by the author based on the Encyclopedia of Countries and Cities (2024b).

For all types of armaments, we can observe a significant gap in favour of Egypt; thus, it is difficult to consider the possibility of Ethiopia's military victory under the conditions of third countries’ non-participation in a potential conflict.

The financing of the army depends mainly on the country’s wealth— the stronger the economy, the more funds can be allocated to military spending. Egypt, with a nominal GDP of $398 billion, is more than twice the size of Ethiopia, which has a gross product of $192 billion. Ethiopia and Egypt spend 0.99 percent and 1.23 percent of GDP on military expenditure, respectively. As a result, Ethiopia's military budget is $1.54 billion, and Egypt's is $3.58 billion. Thus, defence spending in Egypt is more than double that of Ethiopia.

In 2023, Egypt’s defence spending declined by more than 20 percent compared to 2022, the largest decline in defence spending in the Middle East region. This picture emerges as Ethiopia’s defence spending has increased strongly in recent years, and the gap between the two countries is narrowing. On the one hand, we cannot yet speak of any balance of power, but the Ethiopian leadership realises that for sustainable peace, it is necessary to prepare for war.

Table 3. Comparison of Ethiopia and Egypt by nominal GDP.

The author compiled the table based on the military balance report (IISS, 2024).

Table 4. Comparison of Ethiopia and Egypt on defence spending.

The author compiled the table based on the military balance report (IISS, 2024).

Overall, we see a situation where Ethiopia is trying to catch up with the military and technical support gap so that its army can compete on an equal footing with Egypt. Still, such a possibility seems unlikely in the near future. Thus, it appears that Ethiopia should be more interested in a diplomatic resolution of the differences. Moreover, the Presidents of Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia agreed on strategic cooperation in the Eritrean capital, Asmara, to protect Somalia's sovereignty (Trifonov E., 2024). In such circumstances, an open escalation of the conflict would end in defeat for Ethiopia.

2.2 Points of confrontation:

a) Struggle over the Nile

The year, 2024, saw an escalation in relations between two East African regional leaders, Egypt and Ethiopia. The escalation took place for several reasons. Firstly, the sensitive issue of the construction of Ethiopia’s Hydase hydropower plant for Egypt infringes on the water rights of third countries. The Hydase hydropower plant is located on the Nile River, which in turn flows to Sudan and onwards to Egypt. According to Egyptian politicians, Ethiopia’s imprudent use of the Nile poses a threat of ecological disaster to neighbouring countries. Despite the UN’s call to come to the negotiations, UN initiatives have failed to produce the long-awaited compromise (United Nations, 2024). Each side of the conflict accuses the other of not offering constructive proposals to resolve the dispute.

b) South Sudan

Ethiopia supported the rebel army of South Sudan (populated mainly by black Christians) against the Muslim Arab government of Sudan in Khartoum, supported by Egypt. The creation of an independent South Sudan was a geopolitical victory for Ethiopia.

c) Sudan Civil War

Since April 2023, the civil war in Sudan has been ongoing between the country's military government (Sudan Armed Forces), backed by Egypt, and the so-called Rapid Reaction Force, based on the black Janjaweed militia, supported by Ethiopia.

d) Somalia and Somaliland (landlocked)

Another important reason for the rising tensions is Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland, an unrecognised part of Somalia that is not subordinate to the official government. Ethiopia’s motivation is obviously the geopolitical interests of a landlocked state. After the recognition, Ethiopia gained access to the territory to build a naval base in Somaliland and deploy its military (BBC News, 2024). In turn, Egypt sent a military contingent to Somalia to maintain the balance of power in the region.

3. Areas of cooperation.

According to official Egyptian sources, “Egypt and Ethiopia are bound by distinguished economic relations, thanks to the Egyptian investments in Ethiopia in different spheres, including El-Sewedy Cables Factory (with investments that roughly hit $1 billion). There are also joint ventures between Egyptian and Ethiopian companies in the fields of agriculture, meat export, and meat processing, among others” (State Information Service [Egypt], 2024). Egyptian imports to Ethiopia exceed $100 million, while exports are less than $20 million. Thus, the total trade volume between Egypt and Ethiopia is very small. The share of Ethiopia’s exports destined for all African countries was 15.9 percent. The main African buyers (in % of the value of goods shipped to Africa) are Somalia (52.6%), Djibouti (21.5%), Sudan (12.4%), Kenya (2.5%), and South Africa (2.1%). These countries received 91.1 percent of all goods Ethiopia supplies to the African market (“Youth and the future of Ethiopia”, 2024).

Ethiopia purchased about 13.1 percent of its total merchandise imports from African countries. Among the suppliers (in % of all goods sourced from Africa) are Morocco (38.9%), Egypt (31.7%), Djibouti (17.6%), South Africa (6.1%), and Kenya (4.6%). Imports from the five listed countries accounted for 98.9 percent of all imports from the African continent (2021/2022) (“Youth and the future of Ethiopia”, 2024).

Cultural co-operation between Ethiopia and Egypt, is primarily developed through the Ethiopian Church, which maintains close ties with its Egyptian co-religionists (Coptic Church).

4. Conclusion.

Thus, the acute geopolitical rivalry between Egypt and Ethiopia in North-East Africa has deep historical roots and is based on undoubted material and cultural factors. Moreover, the acuteness of this rivalry is exacerbated by the small amount of economic and cultural ties between the two great African states. Perhaps it is time for them to shed the image of an enemy, seek common ground, and construct the image of a friend in a united Africa. This construction could possibly be based on a common cultural history (‘Pharaonism’ as a common civilisational heritage of Ancient and Ancient Egypt), as well as on related linguistic ties (Amharic, the state language in Ethiopia, is a member of the group of Semitic languages, as is the Arabic language of Egypt). For the successful economic and social development of Northeast Africa, the entire Nile Valley should not become a sphere of rivalry but a sphere of co-operation between Egypt, Ethiopia, and a peaceful Sudan that has ended the civil war. This is economically and politically more favourable for both states, which do not belong to the world's most developed nations but spend heavily on military expenditure. Political realism has worn out its welcome; geopolitics does not work without economics. Moreover, the historical image of an ‘enemy’ in this case (in the absence of common borders and, consequently, real territorial disputes) has a rather virtual nature in modern times. It can be changed to the image of a ‘friend’ with the active development of Egyptian–Ethiopian scientific and cultural ties.

References:

BBC News. (2024, October 15). Ethiopia signs agreement with Somaliland paving way to sea access. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-67858566

Encyclopedia of Countries and Cities. (2024, October 11). Ethiopia vs. Egypt army comparison. https://terravisor.com/states/army/compare/ethiopia_egypt

Ermias, H. (2020). The Amharic proverbs and their use in Gǝʿǝz Qǝne (Ethiopian poetry). African Journal of History and Culture, 12(1), 28–34.

Global Firepower. (2024, October 10). Countries listing. https://www.globalfirepower.com/countries-listing.php

Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. Simon & Schuster.

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). (2024). The military balance: The annual assessment of global military capabilities and defence economics 2024.

Ram, K. V. (2009). Anglo-Ethiopian relations, 1869 to 1906: A study of British policy in Ethiopia. Concept Publishing Company.

State Information Service (Egypt). (2024, October 15). Egypt and Ethiopia. https://beta.sis.gov.eg/en/international-relations/bilateral-relations/Ethiopia

Trifonov, E. (2024, October 16). Egypt, Somalia and Eritrea have allied against Ethiopia. https://dzen.ru/a/ZxEslRE5S0yPYE0r

Tsypkin, G. V., & Yagua, V. S. (1989). History of Ethiopia in modern and contemporary times. Nauka: Main Editorial Office of Oriental Literature.

United Nations. (2024, October 14). Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan should negotiate mutually beneficial agreements over management of Nile waters. https://press.un.org/en/2021/sc14576.doc.htm

World Population Review. (2024a, October 7). Muslim population by country 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/muslim-population-by-country

World Population Review. (2024b, October 7). Most Christian countries. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/most-christian-countries

World Population Review. (2024c, October 10). Countries with mandatory military service. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-with-mandatory-military-service

Youth and the future of Ethiopia. (2024, October 15). Ethiopia Foreign trade. https://bigenc.ru/c/efiopiia-khoziaistvo-vneshniaia-torgovlia-af09d6