Between Dependency and Autonomy: Brazil’s Engagement in Global Artificial Intelligence Governance under the US-China Tech Rivalry

Youtong Liu

July 14, 2025

Abstract: As a regional power in Latin America and a representative of emerging economies, Brazil exhibits a strong identification with the “Global South” in global governance. At the same time, its domestic regulatory framework demonstrates normative dependence on the European Union (EU), reflecting a dual emphasis on both “digital sovereignty” and “de-risking”. Brazil’s approach to global artificial intelligence (AI) governance oscillates among the three major paradigms of the United States (US), China, and the EU, seeking a balanced strategy that asserts leadership while remaining pragmatic. This paper first identifies the overall lack of representation of Latin America in global AI governance, along with the region’s simultaneous exposure to both risks and opportunities. Through an analysis of Brazil’s domestic regulation and global summit participation, this paper further reveals the disjunction between Brazil’s domestic practices and global governance discourse, as well as its triple dependency on the three key players.

Since 2022, generative AI, exemplified by ChatGPT and DeepSeek, has been continuously reshaping global value distribution and geopolitical dynamics. Amid the intensifying US-China technological rivalry, the world has witnessed the ongoing failure of multilateralism in global summits such as Seoul and Paris. At present, regulatory and governance power over AI remains largely in the hands of tech giants, whose profit-driven nature places the Global South under structural exploitation. The global anarchy in AI global governance is calling for more assertive and autonomous actions by nation-state actors, both domestically and internationally. As a regional power in Latin America and a representative of emerging economies, Brazil’s engagement in global AI governance offers a significant point of reference for how Latin American and Global South countries might position themselves and act amid the current wave of technological transformation.

1. AI Global Governance Background

At present, global AI governance exhibits a distinctly realist character, reflecting the principle of great power consensus. Three major governance patterns, respectively from the US, China, and the EU, have dominated the landscape. The US model emphasizes corporate autonomy and is characterized by an “administrative-led” approach, aiming to maintain technological leadership while extending its domestic AI governance paradigm abroad. The EU’s governance framework is rooted in its longstanding regulatory standards on data, privacy, and technology, alongside a traditionally risk-averse economic stance. It prioritizes legislation and regulation negotiated among member states over time, but its pace lags significantly behind the rapid diffusion and sectoral impact of generative AI towards society (Mukherjee et al., 2023). The Chinese model, in contrast, externally emphasizes a Global South narrative and demonstrates strong features of technological catch-up and state-led direction, though it remains rhetorically vague and limited to high-level principles. Domestically, it is marked by government leadership, policy continuity, and collaborative participation from enterprises, with ongoing refinement through “preemptive legislation” (Mok, 2023).

Along the global value chain, the upstream segments of AI infrastructure (energy, telecommunications base, cloud storage, etc.) and foundation model have reflected tech- and capital-intensive patterns, turning the global AI race into a contest primarily among great powers. The DeepSeek-led open-source wave has marked a “Sputnik Moment” in the foundation model domain, prompting many countries outside of China and the US to recognize new opportunities for development. Resource-constrained nations have begun to explore strategic AI applications tailored to specific sectors, thereby reducing their dependence on foreign tech giants and envisioning the possibility of cultivating autonomous AI ecosystems (Yeyati & Guilera, 2025). This shift has also brought the concerns of the Global South into closer alignment with those of the EU. EU member states have expressed intentions to ease digital regulation and promote industrial development, invoking discourses of “digital sovereignty” and “equality” for European industrial renaissance (Mui, 2025; Macron, 2025).

For Latin America, 2025 represents a critical window of opportunity to shift from the role of a “passive consumer” to that of an active “participant” with data sovereignty and localized technological applications. However, as seen previously with LLaMA3, the open-sourcing of DeepSeek-R1 does not automatically lead to technological democratization. Sergio Amadeu, a Brazilian scholar and former director of the National Institute of Information Technology (ITI), argued that for countries technologically dependent on the US, this is a moment to formulate autonomous development strategies, yet neither open-source adoption nor isolated legislation can address the deeper issue of sovereign infrastructure, and the achievement of digital sovereignty requires a systemic approach (Xiong, 2025). Reliance on foreign AI infrastructure, multinational “algorithmic black boxes”, and unclear data ownership all pose risks that Latin America may be subject to “algorithms designed in other countries and distorted in local contexts” (Yeyati & Guilera, 2025). Moreover, the privatized deployment of powerful models may create additional governance challenges, causing “black boxes” at the implementation level of the policy cycle, and exacerbating Latin America’s existing social crises, like transnational crime, firearms, and drug trafficking.

2. Domestic Governance Practices: Digital Sovereignty & Regulation-Based Pattern

As a regional power in Latin America and an active participant from the Global South in global governance, Brazil’s national development plan for AI and its domestic regulatory framework are embedded in the discourse of “digital sovereignty”. Brazil’s domestic AI development actions mainly follow its Brazilian Artificial Intelligence Plan 2024-2028 (2024). This plan aims to promote innovation and efficiency of AI adoption, especially in the public sector (IDS News, 2024). It includes “Immediate Impact Actions” to solve domain-specific problems in society and economy, and “Structuring Actions” to promote long-term computational capability via the development of the Santos Dummont supercomputer.

Under a similar regulation-based pattern of the EU, the Brazilian AI development plan focused on encouraging innovation, safeguarding development space, and protecting human rights. Specifically, its framework includes the proposal of a national “sovereign cloud” to protect sensitive data, and the establishment of a national center for AI transparency and trustworthiness. In terms of development plans, Brazil’s development objectives are focused on digital security, social justice, and long-term infrastructure projects, with less attention paid to algorithmic innovation, academic breakthroughs, etc., reflecting a follower or catch-up profile.

On the regulatory side, there is currently no specific AI law in Brazil. AI governance has been mainly placed under the umbrella of data regulation, aligning Brazil with the EU pattern. In 2020, the Lei Geral de Proteção (LGPD), which is similar to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), was enacted as a localized data protection framework. However, compared to the GDPR, the LGPD places more emphasis on sovereign control of cross-border data flows, local compliance for in-country data processing, as well as the relative independence of legislation and single government ownership (Usercentrics, 2024). In general, the Lula administration has always been wary of transnational technology capital. In August 2024, it issued a ban on X for spreading false information and failing to appoint a legitimate state representative. As a result, the Brazilian government has also attracted Musk’s critique concerning “democracy” and “free speech” (Global Government Affair, 2024). Within the framework of the LGPD, AI governance in Brazil emphasizes transparency, interpretability, and legitimacy, but lacks a specific legal definition of AI and algorithms, regulation of non-personal data, and governance mechanisms for specific AI risks (deep fakes, black boxes, etc.). As a result, while Brazil highlights sovereignty and autonomy in both AI development and regulation, its regulatory model still largely references EU standards, leading to a rule-taker role in AI global governance.

The year 2025 is the last year for the Lula government to push for major policy changes before the elections, making it a crucial period for digital policymaking in Brazil (Covington, 2024). Since 2022, Brazil has been working on the development of the AI Act, following the EU pattern and defining a risk-based approach to regulation. After much bargaining between the government, experts, and stakeholders, the Act was approved by the Senate in December 2024. It is able to apply to all stages of the AI lifecycle, introducing the concept of a “regulatory sandbox” and integrating local priorities (labour rights, environmental sustainability, etc.) with global standards. However, the Act has also been significantly modified under industry pressure, including the exclusion of social media content curation and recommendation algorithms from the high-risk category in order to reduce censorship requirements (Atanasovska & Robeli, 2025). As an extension of domestic governance, Brazil’s engagement in AI global governance may not follow a path of technological catch-up with first-mover regulatory practice to become a “rule maker”. Instead, Brazil’s AI Act is more likely to become a model for the Global South in terms of local adaptation and distributive justice.

3. Global Governance Engagement: Domestic Extension with Global South Identity

In the post-globalization era, negotiations on emerging global governance issues are often discussed through summits. In summit diplomacy, one mode gathers multiple stakeholders to discuss specific issues, mostly in emerging strategic industries. The other one combines head-of-state diplomacy with multilateral institutional platforms, which have the small-grouping and institutionalized characteristics to enhance attention and focus on issues (Odinius, 2021). The outcomes of these summits are often taken to the UN system for reaffirmation and broader consensus-building.

a) Brazil’s Participation in Global AI Summits 2023-2025

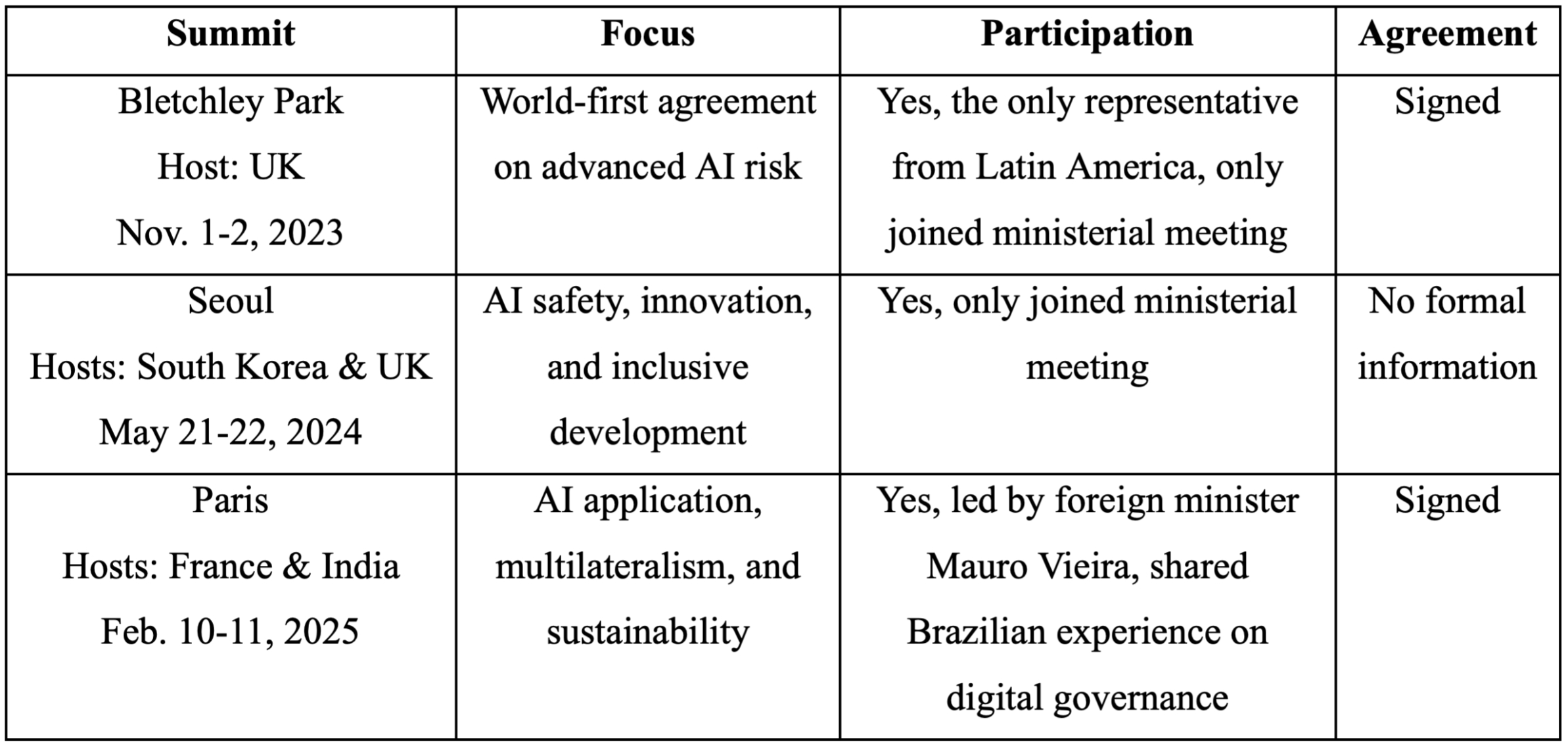

The world-first consensus on advanced AI risk and regulation was achieved at the 2023 Bletchley Park AI Safety Summit. This small-scale summit gathered representatives from 28 countries, the EU, the UN, and selected tech giants (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, X, etc.). Although China was the one that was informally invited by the UK for “unacknowledged attendance”, key players in the AI realm still reached an agreement on the Bletchley Declaration (Stacey & Milmo, 2023). Brazil was also invited to attend this summit as the only representative from Latin America, and signed the agreement with the others together. However, participants are not treated equally at this summit. Despite the consensus of the first day’s ministerial meeting, the head-of-state summit on the second day only included the UK and US and their key allies to insist “democratic values” but without democratization of participation.

This Western-centered summit governance framework continued in Seoul, where Brazil was also present, but with no information about whether it signed any agreements. Brazilian companies were also absent from the signing of the Frontier AI Security Commitment during the summit (Birch & Ozfirat, 2024). It was not until the February 2025 Paris AI Action Summit that this series was expanded from its original mini-summit to a “summit week”. In parallel with the inclusion of the Global South, Brazil’s participation increased. Represented by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mauro Vieira, the Brazilian government and most of the participating countries reached a consensus on the inclusiveness and sustainability of AI. At the meeting, Brazil advocated for AI governance to be structured in a way that promotes development and reduces inequality, expressed its support for UN-centered multilateralism and human rights protection, and shared its experience in digital governance (Garcia, 2025).

Table 1: Brazil’s Participation in AI Safety/Action Summits 2023-2025

Brazil’s participation in other global AI summits is selective and compromised. For nation-state actors, military applications of AI are a key segment in AI global governance. However, the Responsible AI in the Military domain Summit (REAIM), which has now held two editions, did not agree on regulatory action on military applications of AI. By November 27, 2024, 58 countries have endorsed the US-proposed Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy at the 2023 Hague Summit, consisting mainly of rich European and North American countries (US Department of State, 2024). Brazil, like China, neither appeared on the list nor supported REAIM’s “Blueprint for Action” (REAIM, 2024). This may be due to the fact that the high sensitivity of AI military applications has raised the need for autonomous frameworks and policy spaces in the Global South, making it harder to be receptive to Western-led proposals. In comparison, Brazil is willing to accept the OECD-led initiative in the field of social development, namely the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence (GPAI), which focuses on democratic values, human rights, accountability, transparency, diversity, inclusiveness, and privacy (Calvi, 2020).

b) Brazil’s AI Governance in the G20 Summit 2024

In 2024, Brazil held the G20 Rio de Janeiro Summit under the motto of “Building a Just World and a Sustainable Planet”. In the G20 Digital Economy Working Group proposal, “AI for Sustainable Development and Reducing Inequality” is one of the four priority issues as a response to the “double-edged sword” nature of advanced AI in industry and society. In addition, the G20 Ministerial and Leaders’ Declarations of 2024 both affirm a consensus on co-regulation to address the threats posed by AI and to elevate the voice of developing countries (Santos, 2024).

In collaboration with the Brazilian government and UNESCO, the 2024 G20 also launched the Toolkit for AI Readiness and Capacity Assessment. This Toolkit aims to build an assessment model for AI development potential across countries under the values of inclusiveness, equality, and sustainability, attempting to bridge the North-South digital divide through collaborative governance and AI autonomy. Specifically, the Toolkit assessed countries’ AI readiness in six dimensions: national strategy, AI enabler, scientific and educational capacity, legal and regulatory, socio-cultural, labor force and economy. By deepening the significance of AI autonomy and digital sovereignty through quantitative methods, it also contributed to the Global South lens towards AI global governance.

The G20 Summit successfully reinforced Brazil’s role as a “Global South Initiator” in AI global governance by providing a systematic, UN-centered proposal for an AI global framework. It addressed the need for Global South countries to effectively and credibly assess their positions in global value chains for AI development, and shifted the focus of AI global governance from OECD-centered “de-risking” to the capacity-building and development rights of the periphery. However, due to Brazil’s own lag on advanced AI, its G20 institutionalized outcomes lacked rigid binding, more similar to demonstrative guidance than a feasible proposal to implement.

It is also worth noting that while Brazil emphasized “AI autonomy” and attempted to show leadership at G20, China’s impact can often be seen behind. UNESCO’s AI governance framework was first introduced in 2023. By this time, the US had already withdrawn from UNESCO with China filled the leadership vacuum through membership fees and initiatives. According to US former Foreign Minister Blinken, China was seen to be pushing for international rules, norms, and standards for AI and attempting to exclude the US from global negotiations (Nordstrom, 2023). Furthermore, in the smaller summits of the BRICS bloc, the establishment of the AI Study Group and the idea of an AI governance framework were co-promoted by China and South Africa in 2023. The BRICS AI governance initiative highlighted safety, reliability, controllability, and equity, and is seen to be proposed against the “relevant and appropriate, safe, secure and trustworthy” in the G7 Hiroshima process (Moyo, 2023; G7 Hiroshima Summit, 2023). As the BRICS bloc has a tradition of meeting before the start of the G20 to harmonize their discourse, the emphasis on digital sovereignty and equity in development at the Brazilian G20 is likely to be an exhibition of BRICS’ collective voice.

4. Conclusion and Suggestions

Despite a high-profile advocacy of “Global South perspective” and “digital sovereignty” under the G20 framework, Brazil’s reality in global AI governance shows a triple dependency structure. Specifically, Brazil’s domestic data protection and AI regulatory system is highly dependent on the EU de-risking paradigm. At the same time, its global governance engagement relies mainly on the UN system and China-led small group consensus, while its current AI regulatory implementation obligation is mostly taken by US-centered multinational corporations. Currently, Brazil holds up the banner of “regulation localization”, “Southern sovereignty”, and “equal rights to development” at the international level. However, under the lack of originality and precedence in domestic AI governance, it still aspires to a compromise, hedging AI governance solution, and therefore constitutes a mismatch between international discourse and domestic regulation.

For Brazil, moving from “dependency” to “autonomy” is the focus of its strategic period of the year 2025 in AI global governance. On this basis, this paper puts forward the following recommendations: First, strengthen AI infrastructure to promote the consistency of AI autonomy discourse and implementation, and achieve industrial leapfrogging in global value chains. Second, promote the institutionalization of Global South AI governance values in multilateralism consultations, and proactively integrate the resources of the Latin American region and global governance groups such as BRICS and IBSA. Third, leverage its digital governance strengths in areas like labor rights and environmental sustainability to lead legislation on AI for good and social justice, thereby endeavoring to transform into a rule-maker in global governance.

References:

Atanasovska, D. & Robeli, L. (2025, February 26). Brazil’s AI Act: A New Era of AI Regulation. GDPR Local. https://gdprlocal.com/brazils-ai-act-a-new-era-of-ai-regulation/.

Birch, J. & Ozfirat, O. (2024, May 22). Key Takeaways from the AI Seoul Summit 2024. Access Partnership. https://accesspartnership.com/key-takeaways-from-the-ai-seoul-summit-2024/.

Calvi, T. (2020, December 8). Four new countries join the Global Partnership for Artificial Intelligence. ActuAI. https://www.actuia.com/en/news/four-new-countries-join-the-global-partnership-for-artificial-intelligence.

Christine Mui, C. (2025, February 10). How DeepSeek is looming over the Paris AI summit. Politico. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/digital-future-daily/2025/02/10/how-deepseek-is-looming-over-the-paris-ai-summit-00203426.

Covington. (2024, December 9). Key Votes Expected on Brazil’s Artificial Intelligence Legal Framework and Cybersecurity Constitutional Amendment. https://www.cov.com/en/news-and-insights/insights/2024/12/key-votes-expected-on-brazils-artificial-intelligence-legal-framework-and-cybersecurity-constitutional-amendment.

Garcia, E. V. [@Engenio V Garcia]. (2025, February 10). The first day of the AI Action Summit has concluded in Paris…[LinkedIn post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/eugenio-v-garcia-414316157_the-first-day-of-the-ai-action-summit-has-activity-7294850924563316737-x454/.

Global Government Affair [@GlobalAffairs]. (2024, August 17). Last night, Alexandre de Moraes threatened our legal representative in Brazil with arrest if we do not comply with his censorship orders…[Tweet]. X. https://x.com/GlobalAffairs/status/1824819053061669244.

G7 Hiroshima Summit. (2023, December 1). Hiroshima AI Process G7 Digital & Tech Ministers’ Statement. https://www.soumu.go.jp/hiroshimaaiprocess/pdf/document02_en.pdf.

IDS News. (2024, August 15). Brazil’s federal government launches the Brazilian Artificial Intelligence Plan 2024-2028. https://ids.org.br/en/news-post/brazils-federal-government-launches-the-brazilian-artificial-intelligence-plan-2024-2028/.

Macron, E. (2025, February 9). L’intelligence artificielle, dont le développement ne cesse de s'accélérer, bouleverse nos vies par ses immenses pouvoirs [LinkedIn post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/lintelligence-artificielle-dont-le-d%C3%A9veloppement-ne-cesse-macron-arpue/.

Mok, C. (2023, November 7). Global Competition for AI Regulation, or a Framework for AI Diplomacy?. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/global-competition-for-ai-regulation-or-a-framework-for-ai-diplomacy/.

Moyo, A. (2023, August 25). BRICS bloc commits to secure, equitable artificial intelligence. ITWeb. https://www.itweb.co.za/article/brics-bloc-commits-to-secure-equitable-artificial-intelligence/mQwkoq6YpLzM3r9A.

Mukherjee, S., Coulter, M., & Pollina, E. (2023, October 26). EU lawmakers make progress in crucial talks on new AI rules – sources. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/eu-lawmakers-make-progress-crucial-talks-new-ai-rules-sources-2023-10-25/.

Nordstrom, L. (2023, June 30). China, AI and a say on world order: Why the US rejoined UNESCO. France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/americas/20230630-china-ai-and-a-say-on-world-order-why-the-us-rejoined-unesco.

Odinius, D. (2021). Institutionalised Summits in International Governance: Promoting and Limiting Change. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003167341.

REAIM. (2024, September 11). Countries Supporting REAIM Blueprint for Action. https://reaim2024.kr/home/reaimeng/board/bbsNormalList.do?encBbsMngNo=366e794c7a644d756342425668444f393053755142673d3d&encMenuId=4e57325766362f626e5179454e6d6e4d4a4d33507a773d3d.

Santos, B. (2024, December 19). G20 Brazil Summit: A New Inflection Point for the Digital Agenda. Global Solutions. https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/article/g20-brazil-summit-a-new-inflection-point-for-the-digital-agenda/.

Stacey, K. & Milmo, D. (2023, November 2). The great powers signed up to Sunak’s AI summit – while jostling for position. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/nov/02/the-great-powers-signed-up-to-sunaks-ai-summit-while-jostling-for-position.

United States Department of State. (2024, November 27). Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy. Bureau of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability. https://www.state.gov/bureau-of-arms-control-deterrence-and-stability/political-declaration-on-responsible-military-use-of-artificial-intelligence-and-autonomy.

Usercentrics. (2024, June 3). Brazil’s General Data Protection Law / Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD) – an overview. https://usercentrics.com/knowledge-hub/brazil-lgpd-general-data-protection-law-overview/.

Yeyati, E. L. & Guilera S. (2025, February 19). DeepSeek Reveals Latin America’s AI Crossroads. Americas Quarterly. https://americasquarterly.org/article/deepseek-reveals-latin-americas-ai-crossroads/.

Xiong, J. (2025, February 21). How May China Help the World Break Free From US Tech Giants?. The China Academy. https://thechinaacademy.org/deepseek-set-global-south-free-from-u-s-digital-hegemony/.